My first & favorite oceanographic tale (pun intended) wasn’t Herman Melville’s great American novel Moby Dick (1851) but another American cultural masterpiece: Walt Disney’s 1940 animated musical Pinocchio.

You know, the one in which Pinocchio’s father (creator) Gepetto is swallowed by Monstro, the terrible & vicious sperm whale, … and when he finds out, Pinocchio jumps into the sea, and is swallowed by Monstro? I loved it when Pinocchio reunites with Geppetto – in the belly of the whale – and cleverly devises a scheme to make Monstro sneeze, giving them a chance to escape… the rest as they say is … “go watch the movie.”

Anyway, I still prefer the Disney masterpiece which, throughout my childhood, I thought was the real, the original Moby Dick. Then, in high school, I was forced to read the book and, … along came Captain Ahab!

I’ve dedicated a second cycle of coastal paintings to the memory of Ruth West Coombs and all ‘other’ islanders whose stories & histories yet remain to be told. I’ve spent most summers and many winters in the Hamptons and on Nantucket (for 27 years), and until very recently knew little if anything about these others’ histories.

Hats off to Nantucket Historical Association & Museum of African American History – Boston and Nantucket for attempting to re-integrate their stories back into the psyche of a culture that resides on their native land.

Nantucket-born Ruth West (1895–1964) was an artists – a singer and a concert pianist – who was descended from Martha’s Vineyard Wampanoags at both Aquinnah and Chapaquiddick. “She was a member of the Federation of American Indians and performed around New England as Princess Red Feather, ‘the singing princess.’ According to her obituary, ‘She was a descendant of the Indian Chief Massasoit and was a pianist as well as a noted singer. She started piano lessons at the age of nine and when a young lady studied voice in New Bedford.’ She married Mashpee Wampanoag Darius Coombs, who moved to Nantucket with his brother Otis. They are all interred in a family plot in Prospect Hill Cemetery (text courtesy @ACK history).”

More about Wapanoag First Nation Americans https://wampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/wampanoag-history

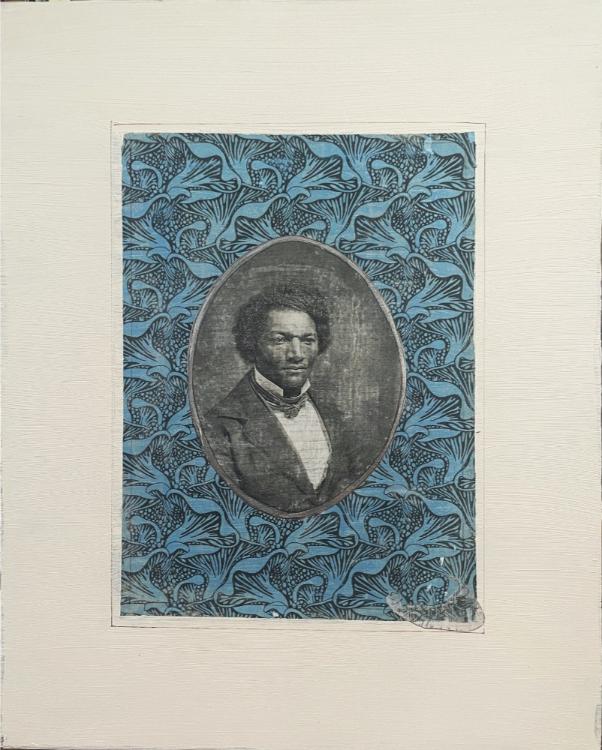

“The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be denounced.” Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was born into slavery, most likely in February 1818 — birth dates of slaves were rarely recorded. He was put to work full-time at age six, and his life as a young man was a litany of savage beatings and whippings. At age twenty, he successfully escaped to the North. In Massachusetts he became known as a voice against slavery, but that also brought to light his status as an escaped slave. Fearing capture and re-enslavement, Douglass went to England and continued speaking out against slavery.

He eventually raised enough money to buy his freedom and returned to America. He settled in Rochester, New York in 1847 and began to champion equality and freedom for slaves in earnest. By then, his renown extended far beyond America’s boundaries. He had become a man of international stature. (Nmaahc Smithsonian National Museum for African American History and Culture)

This is part of an on-going series of ‘other’ islanders with historic affiliations to Nantucket, as an example of a coastal community and its complex histories. A series inspired by my experiences of living on and off seasons on Nantucket Island, for more than quarter of a century, and informed by my research into Nantucket Historical Association collections, over the past two plus decades.

Though Douglas was neither born nor lived on Nantucket, he spoke at the anti-slavery convention held at the Nantucket Atheneu’s Great Hall on August 11, 1841, at the urging of famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. This would be Douglass’ first address to a mostly white audience. He also visited the idland in 1842, 1843, 1850, and 1885.

The Other Islanders is a growing body of portraits to be exhibited as a single work. All works in this series are executed with ink (image transfer) with acrylic on canvas, circa 2021-2022. And, all photos are taken with iPhone 12 Pro in studio daylight setting